The Omnitainment Age: How entertainment became everything, everywhere, for everyone, all at once

TLDR: Entertainment is now everything, everywhere, for everyone, all at once. Discover how Entertainment brands can thrive in this new era.""

Once upon a time, ‘entertainment’ was an industry with fairly clear boundaries. Entertainment mostly meant film, TV, music, and stage productions (until video games came along). But over the last 20 years, the idea of a distinct ‘entertainment industry’ has become increasingly meaningless. The boundaries have dissolved, and the traditional tentpole approach to marketing and merchandising has become obsolete.

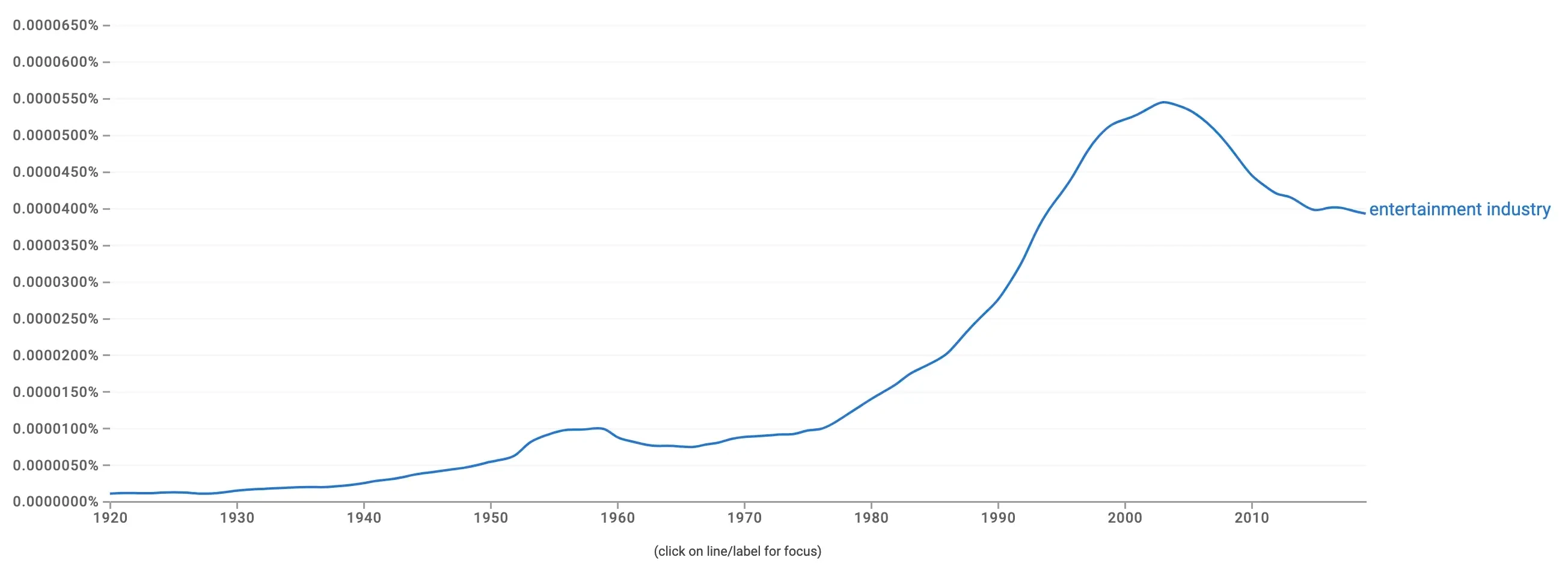

This shift is reflected in data from Google’s Ngram Viewer tool, which shows that mentions of the ‘entertainment industry’ in published books peaked around 2003:

In this article, we’ll take stock of the monumental changes we’ve seen over the last two decades, and look at how entertainment-driven brand extension works in this new, fluid era.

Today, we’re all in the entertainment business.

Look around you. Entertainment brands aren’t just competing with each other for attention, but also the entire internet — the 14 billion YouTube videos, the 249.1 million TikToks tagged #funny, the cute Japanese school kids learning English on Reddit, the US congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez streaming herself playing the game Among Us on Twitch, the non-stop news, the endless emails, and everything else besides.

We can find many of the roots of this brave new world in milestones from the period around that 2003 peak in the graph above:

2002

The first camera phones hit the market, including the Nokia 7650.

2003

Myspace launched, paving the way for today’s socially-networked world, and iTunes rolled out, changing our relationship with music forever.

2004

Facebook was founded. Meanwhile, podcasting emerged as a new medium.

2005

Youtube went online.

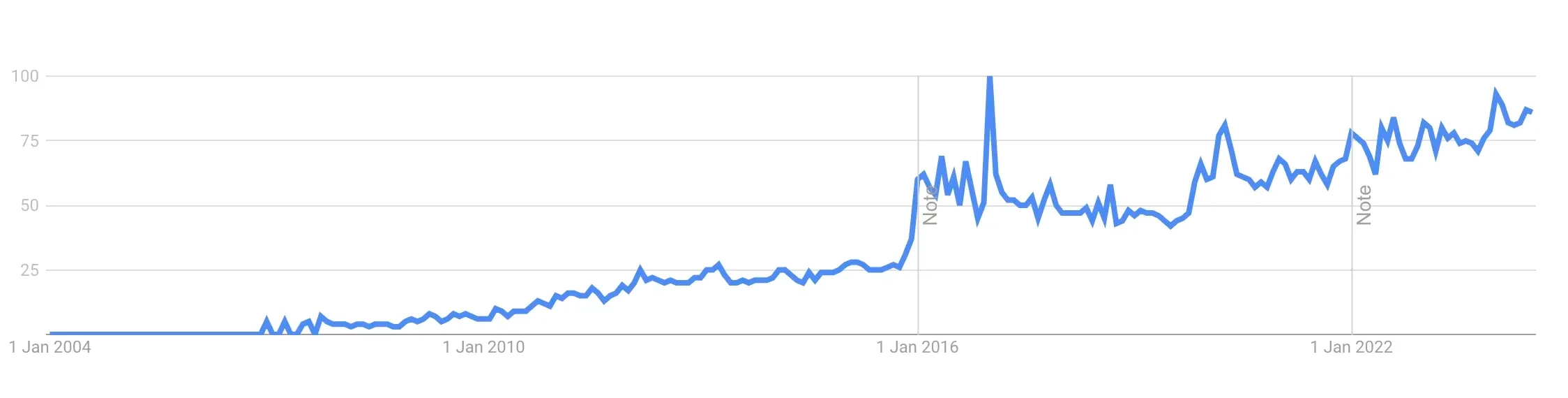

Before these new technologies emerged, a few big players controlled the means of production and distribution. Now, anyone can reach a global audience with nothing more than a device that fits in their pocket. And we’re all on a continual quest for eyeballs and engagement — just look at how searches for “go viral” have grown over the last 20 years:

Below, we’ll explore some key shifts that have been playing out as we’ve entered the Omnitainment Age:

From big releases to infinite, interconnected story-worlds

From marketing to entertainment across industries

From media-driven to merch-driven

From old identity markers to fan-based belonging

From rebel-spirited subcultures to counter-cultural symbols with mass appeal

From film- and TV-centred to game-centred

From box office hits to algorithmic domination

From scarcity to abundance

Transmedia storytelling is the new normal

Your transmedia footprint is the sum total of formats (digital and physical) your brand has been manifested in. As Mohan Sawney, Clinical Professor of Marketing at Kellogg School of Management, explains:

“With transmedia, one overall story is orchestrated in multiple media, each telling a part of the story. This coordinated, unified story experience encourages customers to go deeper into the story as they are drawn into the experience over a multitude of channels used to create a holistic story world.”

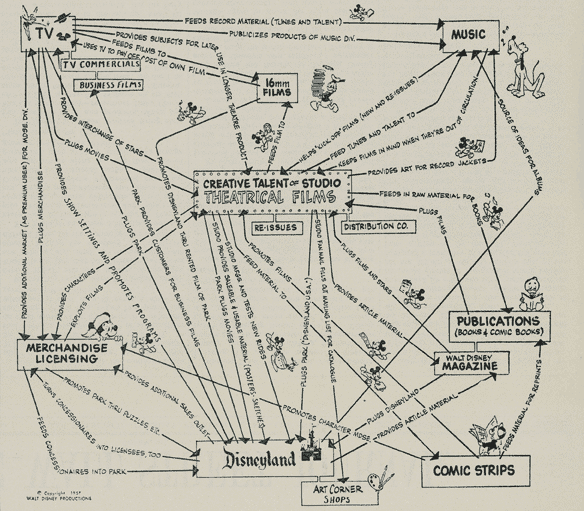

Disney basically had this virtuous commercial circle figured out in the 1950s:

Transmedia stories, or franchises, no longer revolve around a single big release like a film or video game, but rather span an interconnected universe across various platforms — games, TV shows, movies, and more. With a major franchise like Star Wars, fans can explore and engage with the overarching storyline through video games, watch spin-off shows that expand the lore, enjoy theatrical releases that further the core plot, build a LEGO Millennium Falcon, collect limited edition pin badges, and on it goes.

This approach allows for richer world-building, more opportunities for audience engagement, and multiple revenue streams. And it’s increasingly what audiences expect.

Everything is entertainment now

As well as classic entertainment brands expanding their transmedia footprint, businesses from other industries are increasingly “embracing the formats and norms of entertainment.” Deeper connections with audiences and greater cultural relevance are the name of the game.

High fashion beyond the catwalk

In 2022, House of Gucci did well at the box office. And in 2024, The New Look (a series about Christian Dior) started streaming on Apple TV+. We’ve also seen Louis Vitton handing the creative reigns to Virgil Abloh, and then Pharrell Williams — luxury, streetwear, and music all converging in a playful cocktail. Showmanship has always been part of the luxury fashion playbook, but it’s being reinvented for the transmedia age.

CPG brands cutting through the noise

Red Bull have built an entertainment empire over the last 13 years or so. Today, they run over 1,250 sports and culture events each year. They have 16.8 million YouTube subscribers, 23 million Instagram followers, and 13.3 million followers on TikTok. They showed the world that any brand can become a media brand if they’re serious about it.

Where Red Bull started with a cleverly-positioned product and discovered its role as an entertainment brand later, Liquid Death has had entertainment in its DNA from the start. The unignorable name, the punk metal aesthetic, and an early distribution strategy that focussed on music events and festivals. In 2023, Liquid Death became the first headline partner of Download Festival, the UK's biggest rock and metal festival. Recently, they partnered with Amazon to promote superhero series The Boys, and they’re pulling stunts like giving away a fighter jet (an inspired riff on a Pepsi PR failure from the 90s).

Multiplayer shopping

The Chinese ecommerce platform Pinduoduo was the fastest company to reach a $100 billion market cap in history, and has been described as “Disney meets Costco.” Pinduoduo places a strong emphasis on community growth and user participation. It offers features like live streaming and mini-games to keep users coming back. Their business model revolves around group purchasing; bulk-buy discounts encourage users to invite their friends and family to join forces, turning online shopping into a team-based quest.

Traditional entertainment brands understand that attention has to be earned. For brands that hope to grow by entertaining their audience, the experiences, content, and products they offer must be exciting enough to justify expending precious mental energy. People can sense when brands are just phoning it in, and there’s simply too much competition — mediocre ideas and executions won’t cut it.

Let’s get physical

Star Wars really did change everything. As the LA Times reported all the way back in 1999, “After Star Wars, merchandise, which had previously been used to market films, became a thing unto itself, with a shelf life far exceeding the theatrical run that had traditionally set a limit to its viability.” By 1979, two years after the release of the original movie, products included:

Halloween costumes

Records and tapes

School supplies

Lunch boxes

Wallpaper

Watches

Towels

Shoes

Toys (lots and lots of toys)

Fast-forward another 45 years, and it’s now utterly unremarkable to see ‘media brands’ manifested in all manner of physical merch. In this new climate, co-branding and collaborations present infinite opportunities for owners of entertainment IP to stretch into new formats and engage new audiences. In recent years, we’ve seen Star Wars x Le Creuset, for instance.

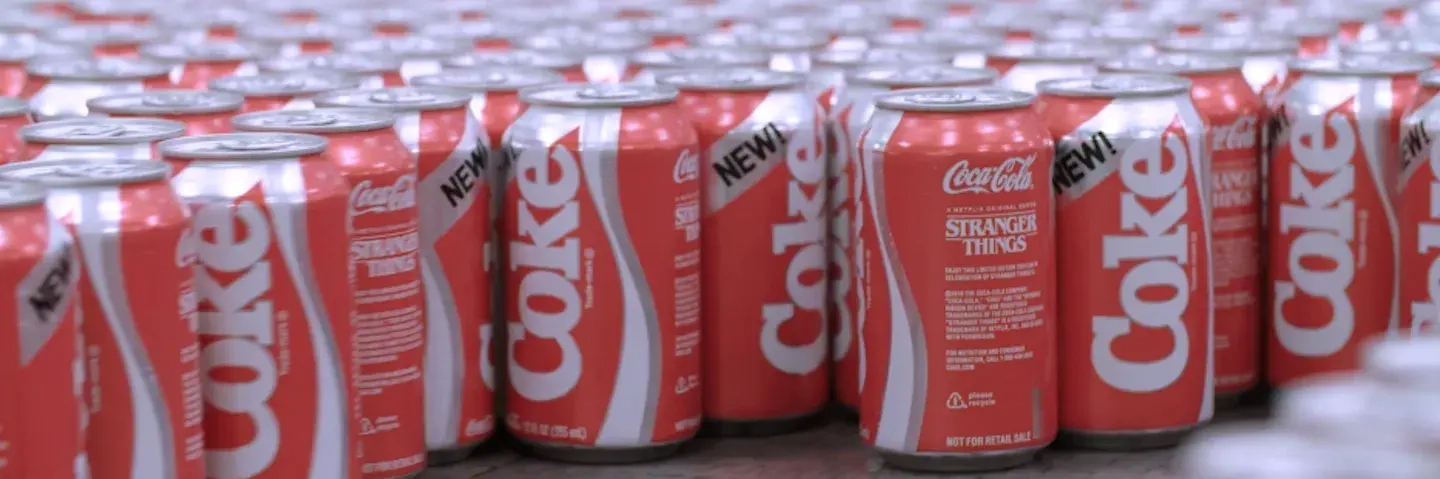

We’ve also seen Coca-Cola release a limited edition re-run of its short-lived New Coke branding from 1985, co-branded with Netflix’s Stranger Things.

And we’ve seen HBO and Mondelēz collaborate on limited edition Game of Thrones cookies.

Transcending demographics

There are no longer neat demographic targets for many of these drops. Traditional sources of identity like age and class no longer provide clear answers to "Who am I?" In their place, fandom offers a sense of belonging.

The audience make-ups of many fan communities may surprise you — LEGO’s growth, for instance, is mostly being driven by AFOLs (adult fans of LEGO). And console gamers in their 30s and 40s now outnumber those in their teens and 20s.

Shows like Bojack Horseman and Rick & Morty tackle complicated, adult themes with kid-friendly characters and animation styles, blurring boundaries and appealing to viewers across age groups.

Having a broad mix of younger and older fans from a wide variety of backgrounds is the norm for most ‘entertainment brands’ today. We're also seeing a shift in how people express their identities through cultural consumption. The rigid subcultures of the past have given way to a more fluid reality. This new landscape allows for a playful exploration of self, often borrowing from various countercultures without fully committing to any single one, as we’ll explore below.

Trying identities on for size

In a recent GQ article, culture reporter Eileen Cartter asked why Gen Z loves Nirvana tees and Thrasher hoodies so much. In our social media age, she writes, “There’s always lots of talk about types of people, whose generalised personas are based on material points such as possessions, behaviours, or interests. A popular garment that becomes linked to a “type” of person can quickly turn into a meme-ified trend.”

There’s a bitesize countercultural thrill available, without the hardcore commitment required by the subcultures of the late 20th century.

In Vogue, the journalist and author Yomi Adegoke has also explored how countercultural signifiers have become shoppable uniforms, available to everyone, everywhere:

“Things that were once deemed alternative are now universal; Dr Martens, once a staple for punks, goths, hippies and skinheads, are no longer just worn by non-conformists. The Thrasher logo from the magazine dedicated to skate culture was once heavily associated with skaters, but alongside celebrities like Rihanna, Ryan Gosling, Justin Bieber and many a model, “normies” started donning T-shirts with it on, too. You don’t have to be a punk to dye your hair acid green and shave the sides into a mohawk.”

As TJ Sidhu, former Style and Culture Editor at The Face, puts it, “When image is everything, and merely a click away, you can be whoever you want to be.” Where fandoms offer belonging, fashion adds self-realisation (whatever that fluid self feels like from one month to the next).

The merch-industrial complex

Writing in GQ, brand strategist Ana Andjelicis and StyleZeitgeist founder Eugene Rabkin argue that merch has become retail’s “main act”:

“Merch has always been a high-margin moneymaker, so a subtle but all-encompassing transformation of retail’s operating principle into merch makes economic sense. Through the process of transubstantiation from a youth culture artefact to a killer business model merch has been turned from its original purpose, meaning and aesthetics into retail's main product category and the only remaining genre. Consumers have learned to buy everything as merch, and there is no going back.”

Merch still signals identity and belonging, just in a more detached, aesthetically-driven way. In this new era, brands can play with merch as art objects imbued with cultural capital. One example offered by Andjelicis and Rabkin is the MSCHF x Tiffany & Co ‘Ultimate Participation Trophy’.

There was a limited edition of 100 trophies available for $1,000 each. The first person to purchase got the 1st-place version, the second buyer got a 2nd place trophy, the third buyer got a 3rd place trophy, and everyone else who purchased one of the remaining 97 trophies got a participation version. Of course, there was rich brand heritage underlying this — it marked the 160th anniversary of Tiffany & Co. making sports trophies by hand at its Rhode Island workshop.

Today, merch can be authentic and ironic all at once.

Despite its ubiquity, merch remains vital and compelling because of its slipperiness. Merch increasingly blurs the lines between categories:

Fashion statement 🌀 Identity badge

Ornament 🌀 Toy

Serious 🌀 Silly

Nostalgic 🌀 New

Commerce 🌀 Art

Physical retail, despite moving largely online, remains hugely relevant, with outsized cultural impact. But as we look ahead to the next decade and beyond, another force is set to shape the entertainment environment…

Will gaming eat the world?

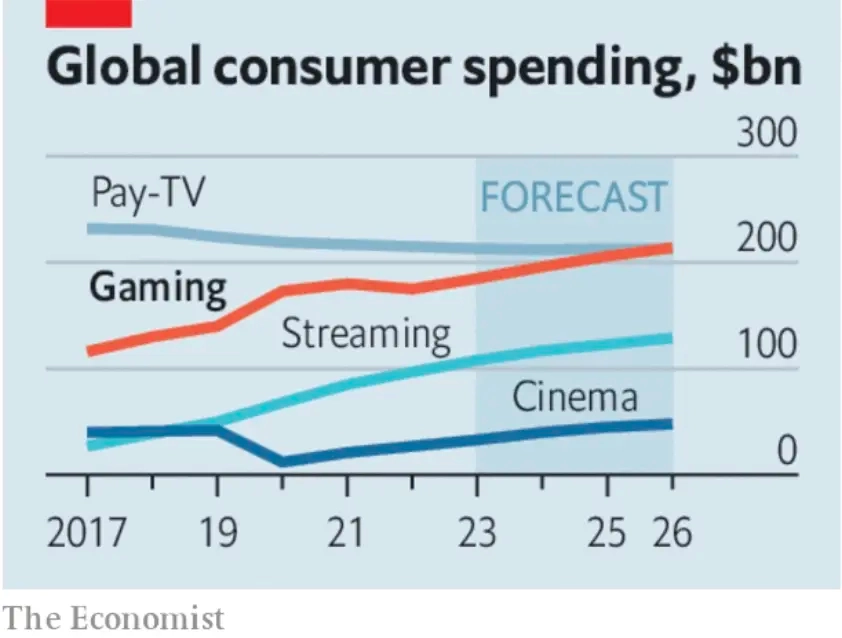

Gaming is MASSIVE. Just look at how much the gaming sector is worth globally:

The second-most successful Harry Potter launch in Warner Bros’ history was 2023’s Hogwarts Legacy — a game, not a film. The 2023 League of Legends World Championship attracted over 100 million unique viewers, comparable to major sporting events like the Super Bowl. The game Cyberpunk 2077 featured Hollywood actor Keanu Reeves in a major role.

Yet, for reasons including the demographic profile of journalists and news editors in traditional media, the biggest games often don’t always feel as much part of collective cultural reality as the biggest films, TV shows, and musical releases.

If you’re not a gamer, it’s easy to dismiss the scale and importance of gaming, or assume it’s just for kids. But, as Blake Robbins, co-host of a podcast about the modern history of the video game business, argues, “If you want to understand culture in the future (let alone influence it and stay relevant!), play games.” Ignoring gaming is, quite simply, commercially irresponsible. As per The Economist, “Media firms that ignore gaming risk being like those that decided in the 1950s to sit out the tv craze.”

How gaming shapes wider entertainment culture

Gaming is increasingly influencing the worlds of TV and cinema. Netflix series The Last of Us (based on the PlayStation game of the same name) was the top TV series of 2023 on IMDB. Universal’s The Super Mario Bros. Movie was the second biggest film of 2023 after Barbie. There are at least 72 more upcoming video-game-based films and TV shows currently announced.

We’re also seeing the virtualisation of physical entertainment experiences, like Universal’s recent partnership with Minecraft, recreating popular theme park rides from Universal Studios within the game.

The worlds of gaming and sport are also converging more and more. This year, a man who’d spent 8% of his waking life playing the game Football Manager was hired as head coach by the Icelandic team Knattspyrnufelag Vesturbæjar. And Sony’s 2023 film Gran Turismo was based on the true story of a teenage Gran Turismo player who won a series of Nissan competitions and became a real-life, professional racing driver off the back of his gaming skills.

Fashion and gaming are increasingly overlapping too. 100 Thieves call themselves “the premium lifestyle brand for the gaming generation,”; they’ve recently partnered with brands like Adidas and Oakley, helping them connect with new audience segments.

Gaming culture has also spawned new platforms like Discord and Twitch; platforms that people have spontaneously started using for other things, from hosting professional communities to jewellery-makers live-streaming from their workshops. In this way, the aesthetics and cultural codes of gaming increasingly leak into other realms of life.

The growth of Esports

Esports has seen tremendous growth in recent years, with Asia leading the charge in terms of popularity and investment. In Asia, Esports is increasingly seen as a legitimate form of entertainment and competition, on par with traditional sports, and is gaining traction among younger audiences. China is the largest Esports market in the world, generating $10 billion in revenue in the first half of 2023, and Esports is gaining recognition at major sporting events like the Asian Games.

The structure of Esports worldwide has become more professional, with established leagues like the Overwatch League and the League of Legends Championship Series. These leagues follow a franchising model similar to traditional sports.

As noted by Boston Consulting Group, “even the largest Esports events are 50x times smaller than the FIFA World Cup, the world’s largest sporting event.” But, they add, “while sports viewership is stagnant, Esports is snowballing.” Currently, only around 15% of the global gaming population watches or participates in Esports, indicating the enormous untapped growth potential that remains.

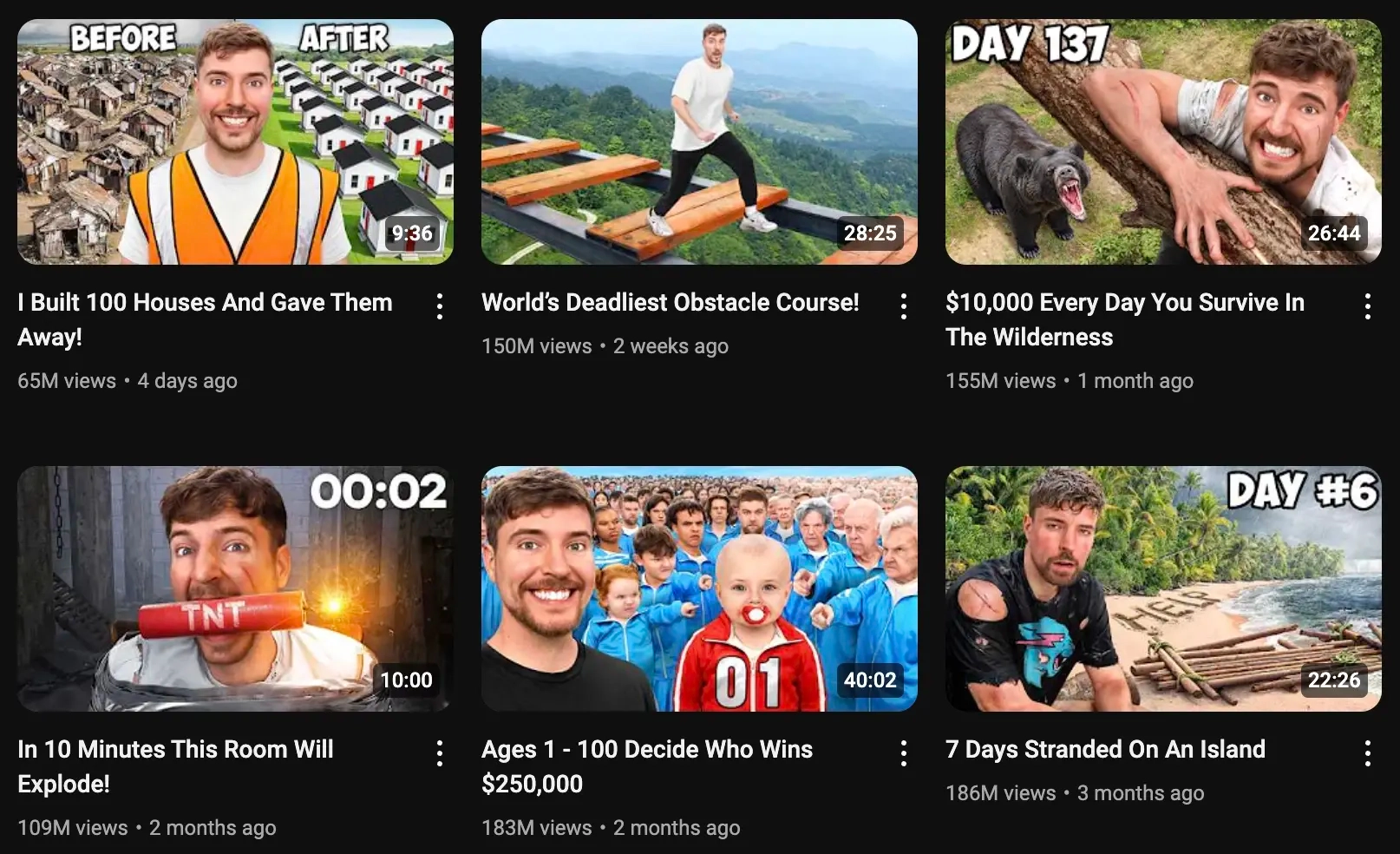

Esports isn’t the only digital-native entertainment phenomenon reshaping the media landscape. Individual content creators have also risen to incredible heights of reach and wealth. Perhaps no one exemplifies this trend better than Jimmy Donaldson, better known as MrBeast…

It’s MrBeast’s world, we just live in it

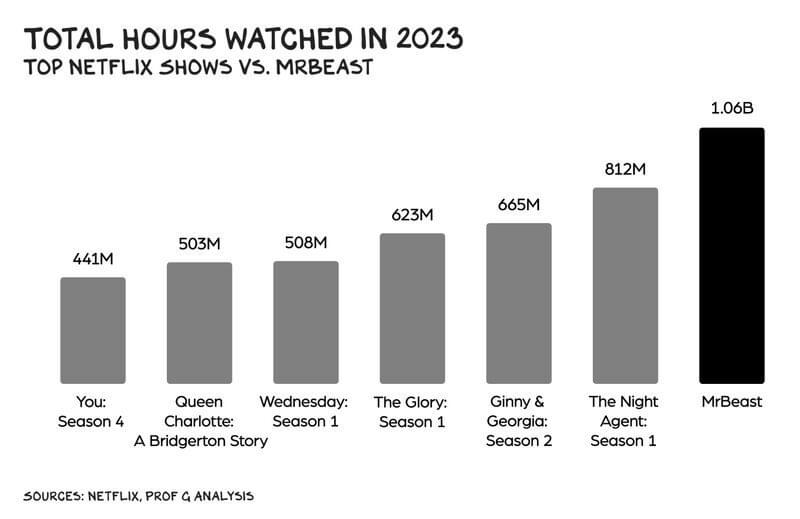

With a blend of viral stunts, elaborate challenges, and giving away a massive amount of money, MrBeast has captured the attention of millions worldwide. He now has the most subscribed YouTube channel on the planet (286m subscribers at the time of writing). Here’s how his total hours watched compared with some popular Netflix shows in 2023, for context:

His commitment to unpicking YouTube’s algorithm has been relentless since he started posting videos on the platform in 2012. His videos are precision-engineered to maximise every important metric — the most popular ones include a real life Squid Game contest, spending 7 days “stranded” on an island, and, more uncomfortably for some, building 100 wells in Africa.

MrBeast is emblematic of the rise of creators more widely. And this new breed DIY media brand is discovering that the biggest business opportunities lie beyond the platforms they’ve built their audiences on.

As creator economy specialist Rebecca Jennings explains in Vox:

“Despite pulling in around $600 million to $700 million per year, according to his own estimate, Donaldson’s production company does not make a profit and does not expect to be profitable this year. Instead, he reinvests the money into his charity channel and his other videos, or his numerous other business ventures. Primary among them is Feastables, the snack brand that once included a chocolate bar called “Deez Nuts” (they’re no longer allowed to use the name after a company called Dee’s Nuts won a lawsuit against it). He’s currently planning Mr. Beast-branded games and apps, and has a deal with the collectible toy company Moose Toys.”

And as reported in The Telegraph, “In September Beast Holdings, the parent company for the business dealings of the YouTube star, applied for a host of trademarks covering cereal fruit, nut and seed-based snacks, as well as candy bars, cookies, breakfast cereals and gummies.”

We’ve also recently seen the Prime energy drink, promoted and founded by YouTubers and Logan Paul and KSI, make over $1 billion in its first year. The hype has faded fast, but as Zoe Scaman has argued, “Being a billion dollar flash-in-the-pan is just fine as an outcome if your goal is to capitalise for a set duration of time, which as creators, is often the case.”

The internet has fundamentally changed the economics of entertainment. The way creators like MrBeast can build a massive audience and extend their brands across a range of physical formats illustrates the new possibilities in what we might call "webonomics" – the new economic principles of the Omnitainment Age.

Embracing webonomics

The pace and scale of change can feel threatening to established industry interests, but the overall effect has been a growth in consumer spending on entertainment. Data from the US shows that the average American spends $1,700 more each year on entertainment since the internet reached mass adoption.

The everything, everywhere, for everyone, all at once nature of the Omnitainment Age might seem overwhelming, but it was already being articulated 20 years ago by Chris Anderson, former Editor-in-Chief at Wired. In his 2004 article ‘The Long Tail’, he wrote:

“Hit-driven economics is a creation of an age without enough room to carry everything for everybody. Not enough shelf space for all the CDs, DVDs, and games produced. Not enough screens to show all the available movies. Not enough channels to broadcast all the TV programs, not enough radio waves to play all the music created, and not enough hours in the day to squeeze everything out through either of those sets of slots.

“This is the world of scarcity. Now, with online distribution and retail, we are entering a world of abundance. And the differences are profound… You can find everything out there on the Long Tail. There's the back catalogue, older albums still fondly remembered by longtime fans or rediscovered by new ones. […] There are niches by the thousands, genre within genre within genre. What's really amazing about the Long Tail is the sheer size of it. Combine enough non-hits on the Long Tail and you've got a market bigger than the hits.”

Whilst he perhaps didn’t fully anticipate the rise of internet-native attention-guzzlers like MrBeast, he was right about the dizzying abundance of content that characterises our new reality. For brands that want in on the entertainment action, the days of relying on media gatekeepers and bricks and mortar retail are over.

As we've seen, the Omnitainment Age has brought about seismic shifts in how entertainment is created, consumed, and monetised. From the rise of transmedia storytelling to the blurring of lines between different industries, from the dominance of gaming to the ascendance of individual creators, the landscape continues to evolve at a rapid pace.

Key takeaways

For brands looking to thrive in this new environment, adapting to these changes is essential. With that in mind, here are nine key takeaways for brands Omnitainment Age:

Focus on growing your transmedia footprint

Use stories, humour, nostalgia, and other emotional levers to draw people in

Sell physical goods direct to consumers online

Question assumptions about your audience

Seek out collaborations that excite and surprise people

Prepare for a world where culture revolves around gaming

Learn from what successful creators are doing

Test and iterate instead of big-bang launches

Let your creatives have fun — audiences can feel it!

Let's talk

Ready to thrive in the Omnitainment Age? Get in touch today to discuss your next project.

Entertainment case studies

Want to see what Skew can do? Check out some of our Entertainment projects: